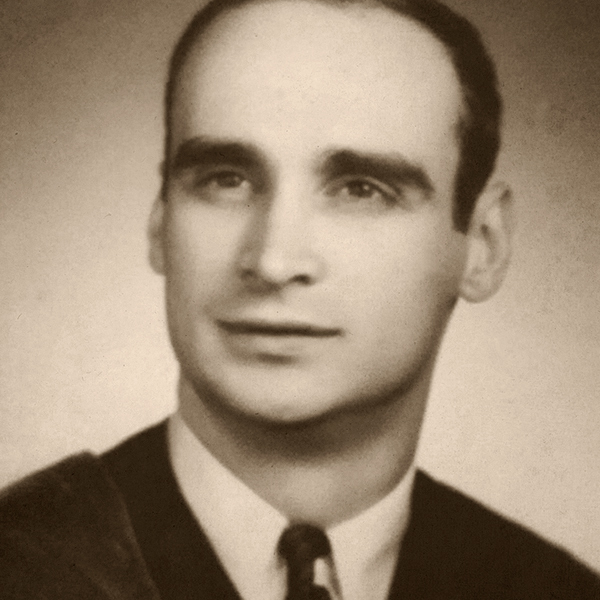

Daniel Lovrinic

Hazleton, Pennsylvania - United States Navy

Written by Spencer Lovrinic

I write this on behalf of my father, Daniel Lovrinic, M.D. His introduction to the military came by enlisting in the U.S. Navy Reserves in 1962, as he entered medical school. After he graduated medical school in 1966 and started his residency in Chicago, the hot years of the war began. Dr. Lovrinic managed to stay within his residency in Chicago until 1968 when he was called into active duty in the Navy. He had arrived in the South China Sea aboard his ship, U.S.S. Galveston (CLG-3), right after the Tet Offensive. I remember him telling me at a young age that his bed was located directly underneath the front Mark 16 battery and how he didn't get a single second of sleep during the first night as the guns were pounding away. After that night, he said the guns never bothered him again and he "slept like a baby."

My father was part of the Medical Corps as a physician, and knew that he would be on the front line for all sailors aboard in case of medical need. One of the biggest trials he faced was performing an appendectomy in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, which saved a sailor's life. However, there were other times where his help could only go so far such as when a sailor fell down a flight of steps, and was rushed to my father for treatment. That sailor died after my father gave all his attempt to save him; dad took that loss hard, and never forgot it. When he came back to the states and was sent back to reserve duty in 1970, and was honorably discharged in 1972. He was able to launch his medical career in California, and some years later moved back home to Pennsylvania.

As I was growing up, I became aware of his service when I found a shoe box with some memorabilia from dad's Navy days, including his white gloves, rank pins, and garrison cap. Unfortunately, this was at the same time his Alzheimer's diagnosis in 2007. Questions were not always met with answers, as the disease took its toll on his brain. Sometimes he would tell me stories, such as when he watched battles take place from the ship, the appendectomy procedure, and how a sailor died after falling down a flight of stairs. Other times he would simply say "I don't remember." I asked my mother about his time in the Navy, where she would say that he never talked about it, except to other veterans.

Year after year, the disease kept progressing and his condition became worse and worse. Between my mother and I being his caretakers, the suffering and stress on both ends became heavy to the point where my father was admitted to a nursing home. We tried to take comfort in knowing that it would be best for all of us; however, the unexpected emotional compromise came when he was found crying in his bed. When I was there with my father during times of distress, he would say that he just realized his mother was dead (Alzheimer's puts its victims in a strange reality); but when the physician in charge asked him what was wrong, my father said "Vietnam." Immediately, my mother asked to get my father assessed for PTSD. Once that diagnosis came through I was shaken to the core once again. Here was a man who couldn't remember my face or name, but still remembered the horrors of war decades later. He never showed any signs of PTSD while I was growing up, maybe he kept it hidden; unfortunately I'll never know. Now, when I hear about the Vietnam War, I only think about how my father never fully came home.